Fans have been used since prehistoric times. They are a natural companion in hot weather. Fans can be as simple as a palm leaf waved in front of the face to keep a person cool or made of elaborate materials like gold filigree or carved Mother of Pearl. The earliest known fans were called screen fans or fixed leaf fans, but much of what we know of the earliest fans is based upon conjecture.

Some of the earliest known fan survivals have been from Egyptian tombs. In fact, in Tutankhamun’s tomb some exquisite fans intricately worked in gold were found which included the remains of ostrich feathers. The discovery was all the more fascinating, because the fans that were found matched those that were depicted in paintings on tomb walls indicating that they were the everyday accoutrements of the king and his family.

However, fans such as these would also have been as much a status symbols. Richly adorned with precious stones or glass faience and ornately decorated with scenes of battles, domestic life or recreational activities, they represented the peak of power and influence and eloquently expressed their owner’s importance. Smaller, hand held versions of these fans, made of palm fibre, were used for everyday purposes, especially the building up of domestic fires. In almost all kitchen scenes and models there is usually at least one busy figure engaged in fanning the flames.

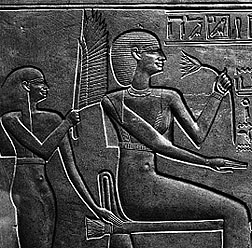

All over the world the plumage of beautiful birds has always been coveted. For thousands of years birds have been kept in cages not only for their song, but also for their beauty and their flapping wings were known to create a breeze. The birds would also flap their wings, creating a cool breeze. The association between birds and fans can clearly be seen in the picture at the top of this page. The fan being held by an attendant of the Lady Ashait (11th Dynasty, 2050 BC) is clearly in the form of a bird’s wing.

This link between birds and fans was not restricted to Ancient Egypt. In the sub-continent of India the Hindi generic term for a fan is ‘pankha‘, from ‘pankh‘ meaning a feather or a bird’s wing. In China the archaic symbol for a fan looks like, and means, ‘a bird’s wing’, and the newer word ‘shan‘ means ‘feathers under a roof’. The Japanese language has similar meanings for the word ‘fan’.

Fans in China have a long history. Probably the earliest Chinese fans discovered so far are two woven bamboo side-mounted fans (second century BC), excavated from the Mawangdui tomb near Changshi in Hunan province, but fans certainly existed in China long before that date.

The first Chinese fans/hand screens were probably of feathers, like many other early fans, and have not survived. At one stage peacock feathers were employed, then, to economise, silk was used and sometimes silk tapestry (kesi). They were sometimes curved at the tip to create a better breeze. Both sexes carried fans in China and detailed regulations accorded a specific type of fan to each rank and person. The fan was used in ceremonies and could also be used to shield one’s face when passing dignitaries of equal rank, thus averting the necessity of endless greeting rituals.

It is now thought that the folding fan was invented in Japan and taken to China sometime in the 9th century. The folding fan was then quickly adopted for everyday use. However, in China, the screen fan still continued to be used throughout society.

Roman ladies had fans, and even Romano-British are known to have used circular fans. A sculptured tombstone in the Carlisle Museum indicates this quite clearly, showing a lady (c AD250) holding a large round fan with radiating ribs; there is further evidence of this type of fan from a 4th century Roman sarcophagus at York, in which a pair of ivory handles were found and a reconstruction of the object was carried out by archaeologists. It would appear that, from antiquity onward, the fan in fashion assumed a dual function, that of status symbol, and that of useful ornament.

Fans in the Americas were like those elsewhere throughout the world, were dominated by the use of birds’ feathers. To the Aztec, Mayan and South American cultures, feathers often had a religious significance, and they were expert in their use in various art forms. Because of their perishable nature, little of this art has survived. However, one fan owned by Montezuma, the Aztec emperor of Mexico is preserved in the Museum of Ethnology in the Hofburg, Vienna. It is one of six pieces of the Montezuma Treasure sent over by Cortez to the Habsburg king Charles V of Spain in 1524.

Europe’s earliest surviving fan is preserved at the basilica of St John the Baptist at Monza, near Milan. It is in the form of a flabellum or ritual fan, presented to the basilica by Theodolinda, the 6th century Queen of the Lombards. This unique remnant made of purple (the colour of royalty) vellum and decorated with gold and silver ornaments, like a similar fan in Florence, known as the Tournus Flabellum.

Queen Theodolinda’s fan still retains its wooden box and silver mounted handle. It was not widely known until 1857, when its existence was publicised by the Victorian architect William Burges. There is a third flabellum, that of St Sabino, a 6th century bishop, that is still in the treasury of his cathedral in the South of Italy and a mediaeval leaf in the British Library.

Sources:

- ‘Fans’ by Nancy Armstrong, Published by Souvenir Press, 1984

- ‘Fans’ by Susan Mayor, published by Charles Letts, 1990